“Heel” is a simple word. A body part, or a part of a shoe. As a verb, the act of repairing a shoe or a command instructing a leashed animal (usually a dog) to follow closely behind its owner.

“Heel” is a simple word. A body part, or a part of a shoe. As a verb, the act of repairing a shoe or a command instructing a leashed animal (usually a dog) to follow closely behind its owner.

Then there’s “heal,” which is a more complicated verb. When it comes to physical injury, the definition is “to cause (a wound, an injury, or a person) to become sound or healthy again.” The implication is that the thing or person being treated will be somehow restored. Sample sentence? “He would wait until his knee had healed.”

Then there is the second definition: “to alleviate (distress or anguish)” What it suggests is a lessening, an accommodation of sorts but not a restoration. Sample sentence? “Time can heal the pain of grief.”

Which is to say, the griever becomes far better at coping, more adept at getting through a day, open to the idea of living, laughing, loving. Never wholly repaired. Ever. Like an aging body, it will always hurt.

I’m surprised more people don’t seem to understand this about grief. Hasn’t loss touched a great number of us? Any episode of “This is Us” or the myriad doctor shows revisit the subject time after time. True, the passing of the elderly may cause less pain, though that is also fungible. Lives cut short are always a shock to the system.

Yet most people are supremely awkward around grievers. Some feel compelled to share their grief stories. Others want to flee. I get it. Listening, just listening, is hard. Being around people in pain is a colossal downer.

Writers are natural grievers. In the effort to tell stories that resonate, we must tap into universal experiences that include joy and hope but also pain and loss. We are required to feel what our narrators feel. Further, we are by nature somewhat solitary. Isolated at times by our own unruly emotions, we must rely on whatever words we have at our disposal, so that we may reach out, connect and find the truth in our own one-of-a-kind process. Such efforts may benefit others. It definitely benefits us.

As does IRL (in real life) contact. Americans may be bad with words but they are terrific huggers. Hugging isn’t for everybody and hugging everybody isn’t for me. I’m squirmy in the embrace of strangers. My family wasn’t overtly physical, although they were never at a loss for words. I’ve been a widow for eighteen years. My sister didn’t hug until the very end of her life. Being folded into an embrace is still a novelty for me.

I don’t mind it, though. It feels as if I’m connecting to something. To another being. To life.

Speaking of connecting, I know far more people now than I did when my husband was killed. Although many of these people remain virtual, others do not. They’ve stepped up. Not only are they reaching out to me, some are determined to get me out of the house. I have (what is for me) a crowded social calendar. It’s exhausting but it’s not a bad thing. I try to accept as many of these connections as possible. I’ve even done my own outreach, making dates and planning to fly off to see distant friends. That’s some sort of record.

Still, I try not to get ahead of myself. Grief drains me. I am often tired. I do practice what my friends call self-care. Less wine, less sugar, more protein, lots of exercise and the aforementioned social engagements. I am lucky to be able to do so and I don’t take that advantage for granted. I’m even grateful to keep busy with the paperwork that arises when one is solely responsible for packing up another’s life.

I’m not a patient person and age has only aggravated my impatience. I want to get on with things. Grief has other ideas about the how and the when, confounding the best laid plans.

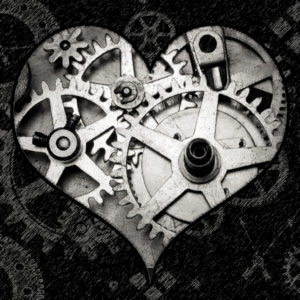

I don’t entirely control my broken heart’s repair. For the foreseeable future, grief is the master. Where it leads, I follow. I heel, so that I can heal.

I have been absent awhile, dear friends, fighting a battle alongside my brave sister, a battle we could not win. After nine weeks of caretaking at my house, she passed away at the very end of November, the victim of a particularly acute form of pancreatic cancer.

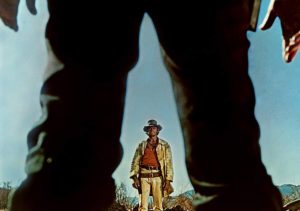

I have been absent awhile, dear friends, fighting a battle alongside my brave sister, a battle we could not win. After nine weeks of caretaking at my house, she passed away at the very end of November, the victim of a particularly acute form of pancreatic cancer. The old man might have been asleep. His beat-up and mud-stained cowboy hat was pulled so low his face sat mostly in shadow. Maybe he’d been watching my approach. I didn’t know, didn’t care. I’d been driving for hours. I was hot, tired, and irritated. And maybe a little nervous.

The old man might have been asleep. His beat-up and mud-stained cowboy hat was pulled so low his face sat mostly in shadow. Maybe he’d been watching my approach. I didn’t know, didn’t care. I’d been driving for hours. I was hot, tired, and irritated. And maybe a little nervous.